South Africa’s democratic transition in 1994 was heralded as a triumph over the brutal apartheid regime. Yet, nearly three decades later, the shadow of apartheid continues to loom over the nation.

The formal end of apartheid did not dismantle the systemic inequalities embedded in its structure. Instead, South Africa finds itself mired in neo-colonialism, where economic apartheid and structural inequality persist, keeping the promise of true liberation elusive.

Economic power

Economic power, the lifeblood of apartheid’s control, remains concentrated in the hands of a white minority and multinational corporations.

Land ownership is one of the most glaring legacies of this imbalance. Despite Black South Africans comprising the overwhelming majority of the population, a 2017 government report revealed that 72% of private farmland is still owned by white individuals.

Efforts to redistribute land have been slow and fraught with challenges, leaving millions landless and economically disenfranchised. This enduring inequality is emblematic of a broader neo-colonial structure where wealth remains tied to historical privilege.

The domination of South Africa’s key industries by multinational corporations further entrenches this reality. Companies like Anglo American and De Beers, which thrived during apartheid, continue to profit from the country’s mineral wealth while the majority Black population bears the social and environmental costs.

The Marikana Massacre in 2012 is a tragic example. When miners at a platinum mine owned by Lonmin protested for better wages and living conditions, they were met with lethal police force, resulting in the deaths of 34 workers. This incident starkly illustrated how economic exploitation, reminiscent of colonial systems, persists under the guise of post-apartheid governance.

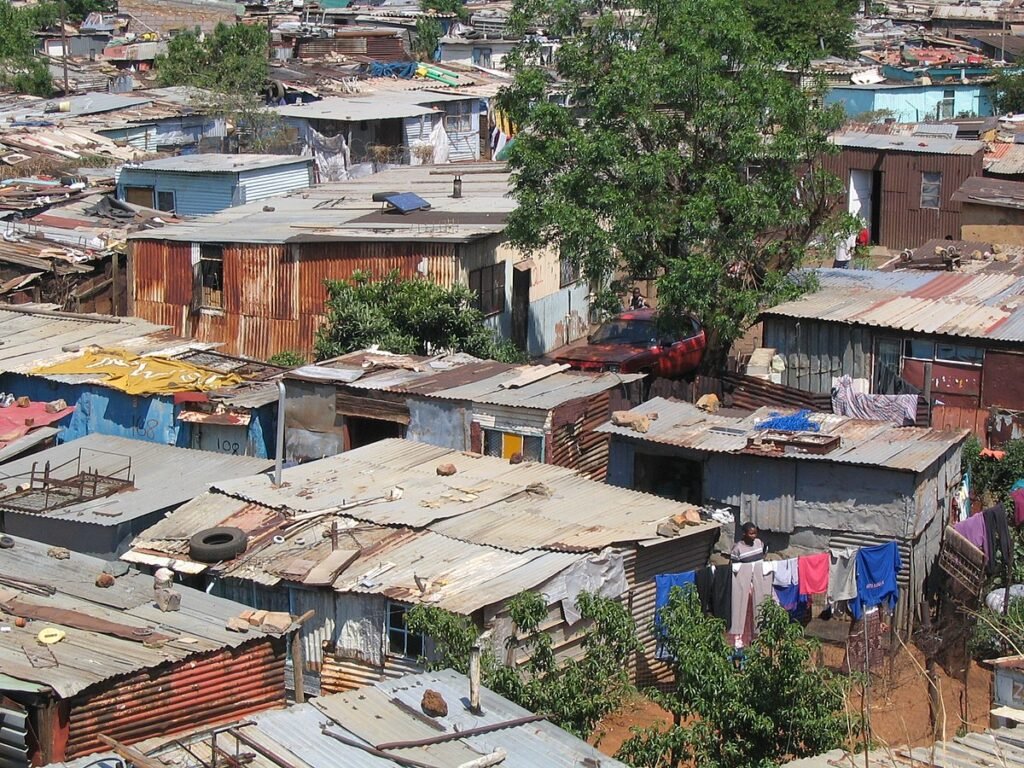

Service delivery in South Africa mirrors apartheid’s spatial and economic segregation. Wealthy suburbs, predominantly inhabited by white citizens, boast excellent infrastructure and amenities, while historically Black townships like Soweto suffer from poor access to electricity, clean water, and sanitation.

These disparities are compounded by high levels of youth unemployment, which disproportionately affect Black South Africans.

Education

The education system, another relic of apartheid, perpetuates inequality. Former “Model C” schools, catering mainly to white students, receive better funding and resources, leaving schools in Black communities unable to bridge the gap.

The Fees Must Fall movement of 2015–2017 highlighted these systemic barriers. Students protested against the high cost of education and the Eurocentric nature of curricula, demanding a transformation of the higher education system to reflect and serve the majority Black population. Their struggle underscored the continuing exclusion of Black South Africans from opportunities critical for upward mobility, further perpetuating economic apartheid.

Neo-colonial entrapment

The persistence of these inequities is deeply tied to South Africa’s entanglement with global neoliberal systems, which prioritize profit over people. The nation’s reliance on foreign investment and trade agreements often constrains its ability to implement redistributive policies that would address these inequalities.

This neo-colonial entrapment ensures that the economic power dynamics of apartheid remain largely intact, even under a democratic government.

South Africa’s post-apartheid reality is a sobering reminder that political freedom without economic emancipation is hollow. To achieve genuine liberation, the country must dismantle these neo-colonial structures, prioritize equitable land redistribution, and invest in education and infrastructure that empower the majority.

Without these transformative measures, the dream of a free and equal society will remain an unfulfilled promise, overshadowed by the enduring legacies of apartheid and colonialism.