For nearly four decades, President Yoweri Museveni and his ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) have maintained a stranglehold on Uganda through a deeply entrenched unitary system of governance. His rise to power in 1986 was heralded as a new dawn, yet, as history shows, it has since evolved into a dynastic autocracy built on constitutional manipulation, militarisation, patronage, and ethnic engineering.

To defeat Museveni and transform Uganda, we must stop thinking inside the political frameworks he has mastered. The unitary system that exists today is one that Museveni inherited, and one which he has studied and perfected since his days as a junior minister under Obote, and during the administrations of Yusuf Lule and Godfrey Binaisa. This system is outdated, dysfunctional, and easily exploited by the ruling elite. It centralises power in the presidency and sidelines the historical autonomy of Uganda’s federal entities.

The Error of “Uganda” and the Erasure of Federal Identity

The very name “Uganda” was born out of a colonial misinterpretation. The 1900 Buganda Agreement which was meant to be an arrangement between the British Empire and the Kingdom of Buganda mistakenly referred to the entire territory as “Uganda,” a misnomer derived from how Arab traders and early missionaries referred to Buganda.

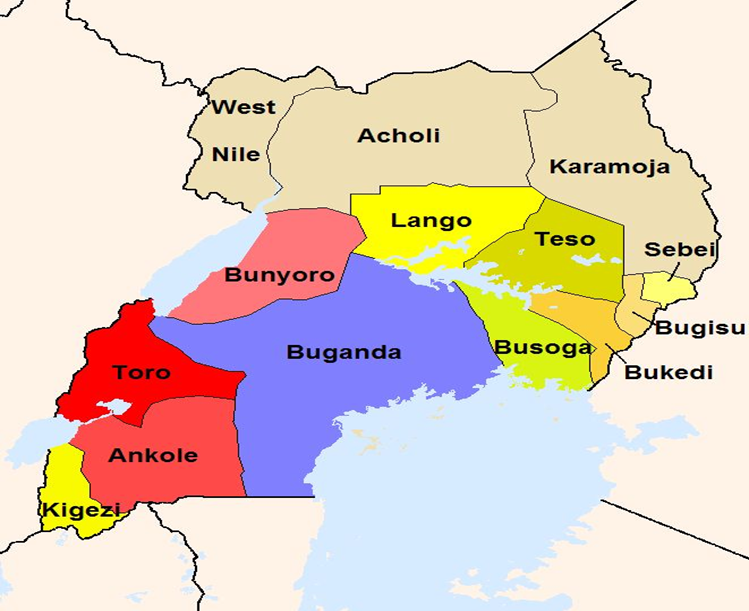

The British, as they often did, chose convenience over cultural and political accuracy. This name stuck and became the official title of the new state upon independence in 1962, when various federal entities including Buganda, Bunyoro, Ankole, Toro, Busoga, and others were forced to enter a union they had neither envisioned nor shaped.

The 1962 Constitution recognized these entities as semi-autonomous federal states. However, in 1967, this constitution was abolished by Milton Obote and replaced with a unitary constitution that completely centralised power. This was the beginning of Uganda’s political decay and the blueprint Museveni would later master and exploit.

Museveni’s Unitary Manipulation

Museveni has consistently moved the goalposts to suit his long-term agenda. Article 105 of the 1995 Constitution, which limited presidential terms, was removed in 2005. Then came the scrapping of the age limit in 2017, allowing a candidate over 75 to contest, paving the way for Museveni’s continued rule even after he reached that age. Furthermore, he has splintered Uganda into over 135 districts, many carved out in regions where NRM enjoys support to inflate parliamentary numbers and consolidate patronage.

Worse still, the Electoral Commission remains under his firm control. He appoints, and can dismiss its leadership, at will – as witnessed before the 2021 general elections. The voters’ register continues to raise suspicions, with inflated numbers failing to match voter turnout or reflect the country’s true demographic reality. Opposition candidates, while technically allowed to contest, do so under brutal intimidation and systemic suppression, enforced by state security forces that serve the incumbent’s political survival.

Why the Opposition Keeps Failing

Despite their courage, most Ugandan opposition groups continue to operate within the same flawed system Museveni dominates. They contest under rules he wrote in arenas he controls. Each time, the opposition underestimates the system and overestimates the extent of its unity. They are divided, overly personality driven, and often intoxicated by the illusion of individual power. This is why every election ends in heartbreak. The system was never designed to hand over power peacefully.

Federalism: Uganda’s Natural Cure

Uganda is not one nation but a union of nations. The pre-colonial federal entities existed for centuries before “Uganda” was even imagined. Federalism is not just a political theory here – it is our original structure.

A return to a federal system, built upon Uganda’s 16 historical federal states, would not only check presidential power but also allow each region to govern its affairs with dignity, autonomy, and accountability. These federal entities are not artificial creations. They are natural, historical, and cultural homelands of Uganda’s peoples. Federalism would enable each to develop according to its needs while cooperating under a unified central government responsible only for defence, foreign affairs, currency, and national infrastructure.

Federalism in Global Perspective

Federalism works. In the United States, power is distributed between states and the federal government, allowing for innovation and regional autonomy. Russia, despite its challenges, maintains stability by recognising its many republics and territories through a federal structure. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) brings together seven emirates under a model where each retains significant autonomy. The United Kingdom, while technically a unitary state, demonstrates federal principles by granting devolution to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, acknowledging their unique identities.

Uganda’s version would be more natural and organic than many of these because our federal regions already exist as distinct cultural, linguistic, and political communities. Unlike in other countries where federal states are artificial boundaries, Uganda’s are rooted in centuries of history, shared traditions, and communal memory.

Conclusion: A Peaceful Path Forward

Museveni’s system cannot be defeated from within it must be bypassed altogether. Uganda’s salvation lies in reimagining its political foundation. Federalism is not a threat to national unity – it is the best guarantee of it. It offers dignity to all regions, brings government closer to the people, and disperses power to prevent another future dictator from emerging.

If opposition forces truly want to liberate Uganda, they must rally around federalism as both a political weapon and a vision of hope. We must stop clinging to Obote and Museveni’s centralised vision and embrace a model that reflects who we truly are: a union of proud nations with shared aspirations.

Let us organise not just to remove Museveni but to build a Uganda that makes such men impossible.

By Mugenyi M. A.K