An artifact is an object made or modified by a human being, and is often of special cultural interest. In the present context, we are talking about objects such as masks, sculptures, textiles, pottery etc. which carry historical, spiritual or social meaning.

Artefacts of this kind serve as a bridge to the past. They embody beliefs or express status, and may function in ritual or governance with meanings tied to specific contexts or to spiritual forces. They are not just “art”, but facilitate communication, the wielding of power, and cultural continuity.

Key functions of artefacts

Significant cultural artefacts have multiple functions and meanings.

Spiritual connection: they often act as channels to the spiritual world, are used in rituals or blessings, as protection, or to honour ancestors (e.g. Dogon masks, ancestral figures).

Social and political status: they show wealth, power, or rank through the materials used in their construction – such as gold and ivory – or through their specific design.

Identity and history: they preserve cultural narratives, beliefs and historical events, connect the generations to each other, and define identity (e.g. the Benin Bronzes).

Function and ritual: they are often worn in performances, used in hunting or as protective charms to ward off evil.

Symbolism: they may carry deep layers of meaning through colour, pattern and animal forms (e.g. spiders for wisdom, birds for female power).

So, an African artefact can be seen as a piece of living culture, packed with symbolic and functional significance far beyond its aesthetic appeal. But its meaning can change. For example, a mask for burial might later be used for display.

Removal and display

Notable examples of stolen African artefacts include:

- Benin Bronzes looted from the kingdom of Benin (now Nigeria)

- The Cullinan diamond from South Africa

- The Ishango bone from the DRC

- The Kabwe1 skull – an ancient human ancestor from Zambia

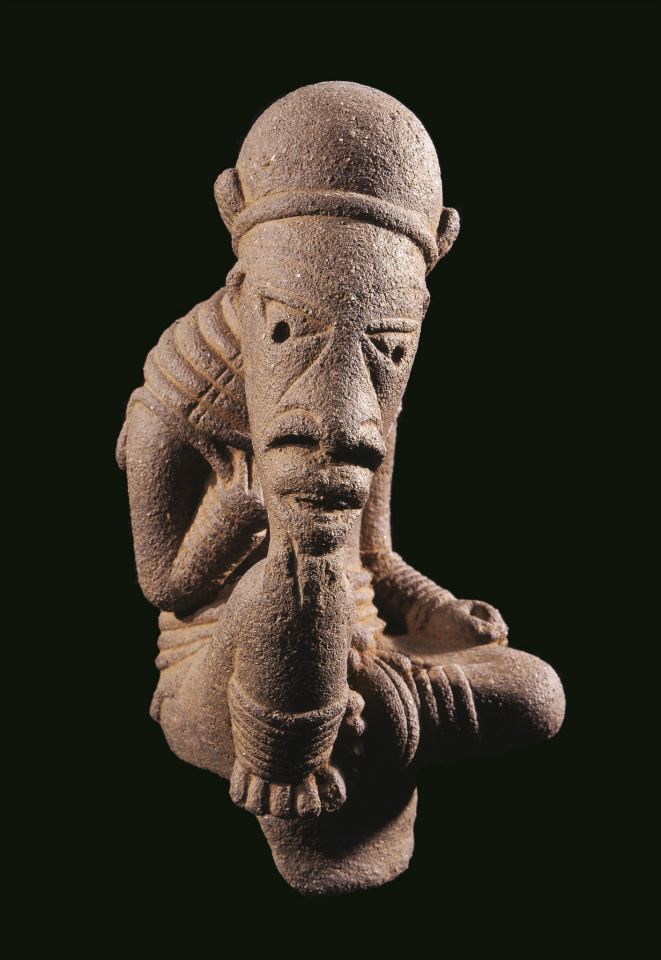

- Nok terracottas from Nigeria

The reasons for the removal of these artefacts – and very many others – include:

Trophies of conquest: many significant artifacts, such as the Benin bronzes, were taken as ‘war booty’ during military expeditions.

Assertion of power: displaying taken artefacts enabled colonial powers to assert their dominance over conquered societies while erasing signs of indigenous cultural and spiritual life.

Academic and curatorial interests: During the 19th and 20th centuries, European archaeologists, anthropologists and collectors developed an interest in the ‘exotic’ and ‘primitive’ arts and cultures of the world. This was often framed within paternalistic or racist ideology, and led to the collection of hundreds of thousands of items for study and display in natural history and ethnographic museums.

Commercial factors: There was a significant commercial market for these objects, with many being sold to private collectors and museums. The trade in these artifacts continues to be a major business today.

Assumed superiority: colonial attitudes held that Europeans were better equipped to ‘preserve’ these objects than the people who created them. It was sometimes mistakenly assumed that the items were of little value to their makers.

Influence of western art: African art had a profound influence on European modernists such as Picasso and Matisse. This further fueled interest in the artefacts – though often without acknowledgement of either the cultural context or their creators.

Conclusion

Today, an estimated 90% of sub-Saharan Africa’s material cultural heritage is held outside the continent, primarily in European museums like the British Museum, the Musee du Quai Branly in Paris, and the Humboldt Museum in Berlin.

African nations are actively seeking the return of these cultural, historical and spiritual items which were looted, seized, or acquired under dubious colonial circumstances. They view their repatriation as crucial for healing, identity and cultural preservation, often through negotiations, legal frameworks, and challenging colonial narratives.

By Godfrey Selbar